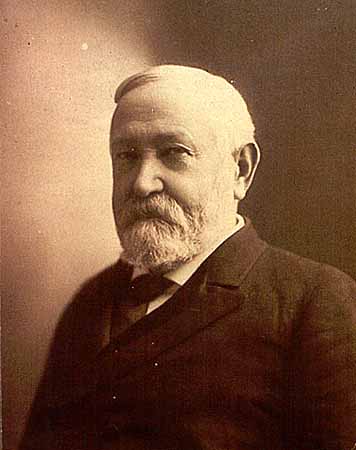

BENJAMIN HARRISON

Biography

“Grandfather's hat fits Ben,” sang the Republicans in the presidential election campaign of 1888. “Ben” was Benjamin Harrison, whose grandfather William Henry Harrison had been ninth president of the United States. In response, Democratic cartoonists drew pictures of a little man in a huge hat—for Harrison was only 5 feet 6 inches tall. Whether the hat fit him or not, Harrison soon got a chance to wear it. He was elected 23rd President and became the second Harrison to live in the White House.

Law, Marriage, and Politics

Harrison studied law and opened a law practice in Indianapolis, Indiana. In 1853 he had married his Farmer's College sweetheart, Caroline Lavinia Scott. They had two children, Russell and Mary. A third child died at birth. A devout Presbyterian, Harrison taught Sunday school and became an elder of the church.

Considering his family background, it is not surprising that Harrison went into politics. His family were Whigs, traditional opponents of the Democrats. But the Whig Party was breaking up, partly because of the issue of slavery, which divided the country. Harrison joined the Republican Party, a newly formed anti-slavery party, and was elected or appointed to several political posts.

Civil War Service

The outbreak of the Civil War in 1861 interrupted Harrison's promising political career. He helped raise the 70th Indiana Infantry and commanded the regiment as a colonel. Although he had no military training, Harrison became an excellent officer. He served in Kentucky and took part in General William T. Sherman's march to Atlanta. He was a fearless soldier and took good care of his men, who called him “Little Ben,” although his insistence on strict discipline made him unpopular. When the war ended in 1865, he held the brevet (honorary) rank of brigadier general.

Return to Politics

Harrison returned to his law practice, his church work, and politics. He soon became one of Indiana's leading lawyers. With success came wealth and social and political prominence. In 1876 he ran for governor of Indiana. The Democrats called him “Kid-glove Harrison” and said he was “cold as an iceberg.” Harrison's chilly, reserved personality was always a political handicap. His opponent, a farmer, won the election.

Nevertheless, Harrison remained the “favorite son” of Indiana Republicans. President James A. Garfield offered him a post in his Cabinet, but soon after, in 1881, Harrison was elected to the U.S. Senate.

In the Senate, Harrison supported civil service reform, a high tariff (a tariff is a tax on imported goods), a strong Navy, and federal regulation of the railroads. In 1887 he ran for re-election but was narrowly defeated.

The Election of 1888

When James G. Blaine of Maine, the leading figure in Republican Party, declined to seek the presidential nomination in 1888, Harrison was chosen as the Republican candidate. Levi Morton, a New York banker, was nominated for Vice President. The Democratic candidate was President Grover Cleveland, running for re-election.

The chief issue of the campaign was the tariff. The Democrats wanted a low tariff or free trade (no tariff at all). The Republicans said that this would ruin business. They wanted a high tariff, to protect American industries against foreign competition.

In the election, Cleveland received nearly 100,000 more popular votes than Harrison. But Harrison won the presidency by 233 Electoral votes to Cleveland's 168.

President

The Republicans controlled Congress as well as the presidency, and in 1890, they passed four important pieces of legislation.

For Civil War veterans of the Union Army, most of whom had voted for the Republican Party, Congress passed the Dependent Pension Act. It provided a pension for any disabled veteran, even if his disability had not been caused by the war.

For businessmen, who had contributed heavily to Republican campaign funds, Congress passed the McKinley Tariff. (It was named for Congressman, later President, William Mckinley.) The McKinley Tariff raised tariffs to record highs. It also raised prices and the cost of living.

Between 1889 and 1890 six new states entered the Union--North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, Washington, Idaho, and Wyoming. Four of these were mining states. For farmers, who wanted “cheaper” money, and silver-mine owners, Congress passed the Sherman Silver Purchase Act. Under this act the government bought almost all the silver mined in the country and increased the amount of silver coined for money.

To help small businessmen and consumers, Congress passed the Sherman Antitrust Act, which was designed to regulate monopolies and prices. The act was not vigorously enforced, however, until Theodore Roosevelt's administration, more than ten years later.

Harrison had promised civil service reform. However, politicians were hungry for jobs, so the spoils system of awarding government jobs for party loyalty continued to flourish.

During Harrison's term of office the United States began to show greater interest in international affairs, especially in Latin America and the Pacific. The first Pan-American Conference took place in Washington, D.C., from 1889 to 1890. All Latin American countries except Santo Domingo (now the Dominican Republic) were present. The Conference organized the Pan-American Union to promote goodwill and co-operation among the American nations.

The Unites States, along with Germany and Britain, established a protectorate over the Samoan Islands in the Pacific. A dispute with Britain and Canada over seal hunting in the Bering Sea was successfully settled. So, too, were disputes with Italy and Chile.

Early in 1893, Americans in Hawaii led a revolt against the native ruler, Queen Liliuokalani. They set up a temporary government and asked the United States to annex the islands. Harrison sent a treaty of annexation to Congress. But his term of office ended before the Senate acted on the treaty, and it was later withdrawn.

Defeat

Harrison ran against Cleveland again in the election of 1892. Harrison's chances were not good. The McKinley Tariff and the heavy federal spending were very unpopular. Government handling of strikes had angered workers. Western farmers were discontented enough to form their own party—the Populist Party—and run their own candidate, James B. Weaver. The illness of Mrs. Harrison (she died two weeks before the election) also limited Harrison's campaigning.

Cleveland won the election, receiving 277 electoral votes to Harrison's 145. Weaver, the Populist candidate, received 22 electoral votes and more than 1 million popular votes.

Later Years

Harrison was not sorry to leave the presidency. Its duties had been a burden to him. He returned to Indianapolis and his law practice. He also spent some time lecturing, as well as campaigning for Republican candidates. He wrote a book on the federal government and the presidency called “This Country of Ours.” It sold widely and was used in colleges as a textbook. In 1899 he served as senior legal counsel for Venezuela in its boundary dispute with British Guiana.

Harrison remarried in 1896. His second wife was Mary Scott Lord Dimmick, the niece of his first wife. They had one child, Elizabeth. Harrison died on March 13, 1901. He was buried in Indianapolis.

As president, Benjamin Harrison was hardworking, honest, and dignified, although never really popular. Since he lacked power in his party, he left legislation to Congress. He tried to steer a middle course on the political, economic, and social issues raised by the industrialization of American life. In this he was much like the presidents who immediately preceded him in office. Political leaders had not yet begun to turn their faces toward the rapidly approaching 20th century.

Reviewed by Richard B. Morris

Columbia University, Editor, Encyclopedia of American History

<<Grover Cleveland (22nd & 24th) | Biography Home | William McKinley>> (25th)